I met Island Records founder Chris Blackwell in the fall of 1972. I was in London to try to convince a young, London-based Jamaican film star, Esther Anderson (she had starred in the just-released Hollywood studio movie A Warm December opposite Sidney Poitier), to do my picture—which was to be my first feature—for free! I had assembled a cast of young, happening French actors including Zouzou (Chloe in the Afternoon), Jean-Pierre Kalfon (Weekend), Pierre Clémenti (Belle de Jour)—who had just gotten out of prison in Italy for possession of hashish—and an unknown Maria Schneider, who had starred opposite Marlon Brando in the soon-to-be-released Last Tango in Paris, to make a movie of our planned trek to the Andes in search of a hallucinogenic root used by the Incas.

When I arrived in London from Paris I phoned Esther. I was focused and on a mission to round out my cast with a “Hollywood” star. She said, “Be at my flat at 7 tonight. We’re going to the movies.” She was bossy in a Joan Crawford kind of way, and she wasn’t asking. It was an order and I was to humbly obey.

She lived in a small but very posh flat in Cheney Row in the very upscale Chelsea. The place was sumptuously embellished with expensive-feeling North African carpets and pillows flaunting a disregard for nationalistic boundaries. Esther was even more exquisitely gorgeous in person than on the screen—piercing dark eyes, long, straight black hair and a warm, ebullient, coffee-toned aura that belied her rising establishment stardom. Elegantly and eclectically adorned in an earthy way that rose above categorizing as “privileged class,” she intoned through her dress and manner a release from the bonds of colonialism in a Far Eastern way that accented her Indian ancestry (her great- grandparents having arrived in Jamaica as indentured servants after England “abolished” slavery in 1839).

She said, “My friends made this movie and we are going to the premiere.”

What threw me was that it wasn’t a limo that picked us up. Rather, Chris Blackwell himself was driving, and the movie’s director, Perry Henzell, was next to him and it wasn’t a Rolls or Jaguar. It was a 1969 Firebird convertible, which, of course, for England had the steering on the wrong side. It was outside the realm of pretension and a minor shock compared to what was in store for me that evening.

Until then I knew Chris by reputation only. He had a larger-than- life aura. He was in a pantheon of music moguls that included Ahmet Ertegun, founder of Atlantic Records (the premier R&B record label); Clive Davis, who ran Columbia Records; Bill Graham, who owned the Fillmore East and West and managed the Grateful Dead and Santana; and Arthur Grossman, who managed Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin. For me Chris had an even greater mystique than any of them.

What the Island Records label represented was a dedication to allowing art to flourish in the domain of popular culture.

Indeed, Island was having huge commercial success with Traffic, an eclectic band that combined elements of jazz and West African music with poetic lyrics and psychedelic rock, and singer- songwriter Cat Stevens, who was selling millions of albums, as well as rock groups such as Jethro Tull, Free, Uriah Heep and Roxy Music. But for me, what separated Island Records from all other labels in the pop music realm was that it was also releasing amazing music that had little or no chance for wide commercial success, yet at the same time it treated the artists producing this music with the same respect as its biggest pop stars. Acts like the experimental electronic group White Noise, idiosyncratic guitarist John Martyn, enigmatic singer-songwriter Sandy Denny, Brian Eno and the list goes on and on.

We were headed to Brixton—London’s West Indian ghetto. This was new to me. I was naive to the extent that I didn’t even know a place like that existed in London.

For all intents and purposes this was a premiere, but I learned several decades later, when an ailing Perry Henzell gave a talk before a screening in Jamaica—in Ocho Rios—that this was actually the third night the movie had played.

The first night no one came. Perry explained that several months earlier another West Indian movie had been released (a first of its kind) and was really bad and people just thought The Harder They Come would be like that. Perry recounted that the next morning he went to the Island office and mimeographed (there were no Xerox machines yet) flyers—and personally went all over Brixton handing them out and imploring people to come. That night the theater was about one quarter full.

When we arrived at the theater that third night—Chris, Perry, Esther and myself—there was a line around the block. Sold out on word of mouth from the night before …

The theater was electric with anticipation. I was the only person of non-Jamaican origin in the audience.

LEE JAFFE: When you brought me to see The Harder They Come in 1972, I knew nothing about Jamaican music. Like so many North Americans for whom it became an instant classic, I too was profoundly influenced by both its desperation and its humor. It opened a whole world of possibilities—in particular, a sense that with music, words could assume a power that might be greater than bombs and bullets. When The Harder They Come was being made, did you have a sense that it could make the type of impact that it has?

CHRIS BLACKWELL: Well, you see, it’s just like making a record. One gets involved because you feel it could be something great. With The Harder They Come I felt particularly close to the subject, of course, by being Jamaican and for my love of Jamaica. So when the opportunity came to be involved with the movie (the director, Perry Henzell, was my friend), naturally I wanted to help. Island Records had Jimmy Cliff on the label, and we felt it could be a great vehicle to promote his career. Jamaica is such a remarkable place. Ethnically it’s so diverse, with many people having some Amerindian DNA and of course European, African and Asian all mixed historically and genetically. I think those diverse influences are what gives reggae its universal appeal. At the time I had confidence that a movie—by bringing visuality to the music—could help expand the reach of Jamaican music. It was a time when there were great artists making compelling records in Jamaica—Toots and the Maytals, who appear in the movie, are a great example—and the soundtrack, from a record company point of view, became a kind of sampler, a way of introducing the music to an audience beyond Jamaica.

LJ: I think for many of us who were new to the music the movie represented a microcosm of a global struggle for independence—a struggle to loosen the chains of colonialism, and of course it was a first introduction to Rasta. Did you feel a closeness to Rasta culture?

CB: Yes, absolutely. An incident happened when I was a teenager that profoundly affected me. I had a tiny sailboat, and I had been taking it out by myself. One time I got caught in a storm. I thought I wasn’t going to make it. The mast had been struck by lightning and the boat had split, and I was holding on to a charred piece of the broken hull and eventually was thrown up against some rocks along a barren stretch of isolated coast. I had been knocked unconscious, and when I woke up I had no idea how long I had been there and no idea where I was. The storm had passed and the sun was blaring and I was scarred and parched and felt like I would be overcome by thirst and dehydration. Then—and it seemed a miracle to me—out of nowhere, there was a Rastaman standing above me, with long thick dreadlocks. He led me to some shade and climbed a tree. He chopped down some coconuts and split them, and I felt like I was being brought back to life. … From that time I have always felt close to Rasta culture. Their concept of leading a life based on being close to nature has influenced me to start an organic farm in Jamaica—it’s called Pantrepant. We have worked with EARTH University in Costa Rica to get it going. We intend to supply the hotels that have been importing all their food, which Jamaica could be capable of supplying instead.

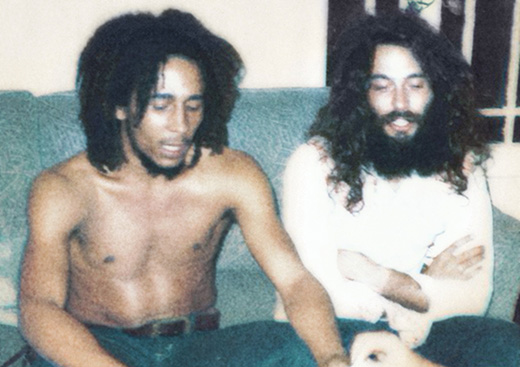

LJ: How did you come to sign the Wailers to Island Records?

CB: What happened at that time—near the release of The Harder They Come—surprisingly, Jimmy Cliff decided to leave Island Records and sign with A&M. It was a bit of a shock because we had been involved in producing the movie and marketing it and of course it was, among other things, a star vehicle for him. Although we had been involved with releasing Jamaican music since the beginning of Island, mostly it was through licensing music from Jamaican labels. Jimmy Cliff was the only Jamaican artist at the time signed directly to Island. I felt with our limited staff—at that time we were only a U.K. company and licensed our music to Capitol Records in other territories—that we didn’t have the necessary resources to give proper attention to a second Jamaican act. So fortuitously, a week after hearing that Jimmy was leaving the label, the Wailers just happened to be in London and called to schedule to meet with me. Truth is, if Jimmy hadn’t just left I wouldn’t have taken the meeting.

LJ: Did you know the Wailers?

CB: Not personally. I was a big fan of their music, but that was the first time I met them.

LJ: What was your initial reaction?

CB: I must say they were an overwhelming presence. Incredibly charismatic. It was all three of them, Bunny Livingston, Peter Tosh and Bob Marley, that collectively and individually exuded this sense of power. I signed them on the spot. I asked them what they thought they needed to make an album and Island provided them the budget and the freedom to do what they wanted. They went to Jamaica and recorded the Catch a Fire album, and when they had finished recording they called me. I suggested they come to London to mix the record and they agreed, and we worked at the Island Studios on Basing Street.

LJ: You have been accused of softening the power of the Wailers’ music by encouraging the adding of elements that until Catch a Fire were absent in Jamaican music, such as blues/rock guitar solos. Those accusations have really bothered me, so of course, when in Kevin Macdonald’s exemplary documentary, Marley, you yourself said that you “pasteurized” the music, I was really annoyed.

CB: [Laughs.] Maybe that was a poor choice of words. However, I felt my job and responsibility to the group once I had committed to them was to help their music and message reach as many people as possible and, of course, there were obstacles beyond those that an English band might have. In the U.S., for instance, radio was a very segregated medium. There were radio stations that would only play music by white artists, and then there were the R&B stations that would only play black music. The problem was that reggae didn’t fit either format. I felt initially that the Wailers would have a better chance to expand their audience beyond Jamaica by adding elements that would have some sense of familiarity to foreign listeners. And, yes, it was my idea that they come to London to do the mixing. The Island studios on Basing Street, from a technical standpoint, were better equipped than anything in Jamaica at the time. I wanted the record to have the production values that would enable it to compete with any of the most successfully commercial records. And, yes, I also suggested they try using a young guitar player—he couldn’t have been more than 20 or 21 at the time—from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, who was living in London and doing session work at our studios: Wayne Perkins.

LJ: I would like to tell you about an experience that has so positively impacted my life ever since. A couple of weeks after you brought me to the theater in Brixton to see The Harder They Come (my first acquaintance with Jamaican music and culture), I was in New York and went to the Windsor Hotel to visit our mutual friend Jim Capaldi [drummer and co-writer in the band Traffic]. Traffic had just played in Madison Square Garden—sadly it was one of their last shows. For me, Traffic signified unquestionably that popular music could be at once powerful, popular, multicultural and high art. It was English poetry and African percussion. It was the blues and it was symphonic.

I got out of the cab at 56th and 6th. It was February and the sky was crystalline with a dark winter sun bouncing off the filthy white remnants of week-old snow. I shivered. I knew my life was at a crossroads. I was 22 years old. I had a stellar cast and crew assembled, which included Maria Schneider, who was the star of Last Tango in Paris opposite Marlon Brando, which had just opened in New York the night before. We were supposed to leave for Chile the next day to start filming what was to be my first feature—an unscripted search for a mystical hallucinogenic root in the southern Andes that the great sculptor Gordon Matta- Clark had told me about. He had come across it on a recent trip to discover his ancestral roots—but the CIA had upset my plans. People were disappearing, including our Chilean co-producer. Soon Salvador Allende was to be assassinated. My world seemed then as uncertain as Jim’s must have seemed to him with his band imploding.

Bob Marley—completely unknown to me—was in Jim’s suite. He had a cassette of the unreleased Catch a Fire. Jim had a boombox and asked Bob to play it for me. With budding dreads, Bob seemed shy and reticent, yet his eyes were keen and radiant—as if nothing could get past them.

What I experienced in the next 90 seconds changed for me indelibly all that would follow. The mixture of sounds: rhythms upside down so new to North American ears; Peter Tosh’s guitar used as percussion instrument; the hipness of the clavinet, which had just then burst on the scene with Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition”; the innovative Joe Higgs–taught harmonies informed by the whole of R&B history; and the interminable power of the poetic—“Concrete Jungle”—a voice that once and for eternity deconstructed the myth of the smiling, docile native blissful in a tropical paradise and the colonialist concept of “noble savage” soon to be gently faded below the horizon like a Caribbean sunset.

With those words and wailing vocals, a voice appeared that spoke for the billion poor of all the shantytowns of this “planet of slums.” Yet for me—the middle-class-bred North American—it was the inclusion of a searing and brilliant lead guitar that created a dichotomy that blazed through any previously impenetrable cultural or ethnic walls. What was that? Who could possibly be playing that? How did that get there in that impeccably mixed recording? Where did that most conscious decision to have this guy come and play on this track come from? How was it that this budding dreadlocks in the room with me advocated for its inclusion?

It was that guitar that said to me (and subsequently to the multitudes of Euro-Americans like me) that this is not a foreign music to be appreciated as the great art it is from a lofty hegemonic viewpoint. This scorching guitar declared unmistakably and interminably that this music was not just of the “Other.” Yes, this music was of all—of “We” …

Boss, I take great exception to your use of the word “pasteurize” to describe the effectiveness of this guitar part. Its inclusion is conceptually diametrically opposed to the notion of “pasteurization.” “Pasteurize” implies a softening. On the contrary, its inclusion makes the music more powerful—more inclusive, more universal. Precisely, it has been your ability to attract the most outstanding culturally and ethnically diverse talents, nurturing them and helping them and the world to share, which signifies your incomparable contribution to popular culture. Did you “pasteurize” Black Uhuru? Sly and Robbie? Burning Spear? Grace Jones? Tom Waits? Linton Kwesi Johnson? Nick Drake? Tricky? King Sunny Ade? Ijahman?

I love defending you—but please stop undermining my efforts.

CB: Well, Jaff, you know, [Wayne Perkins] was there, and I could see he loved what the Wailers were doing, and he had his guitar and you could just feel he wanted a go at it, so I figured why not. And then after he laid down a track, everyone seemed to love it. … Sometimes it’s just being at the right place at the right time—and great music should have no boundaries.

—